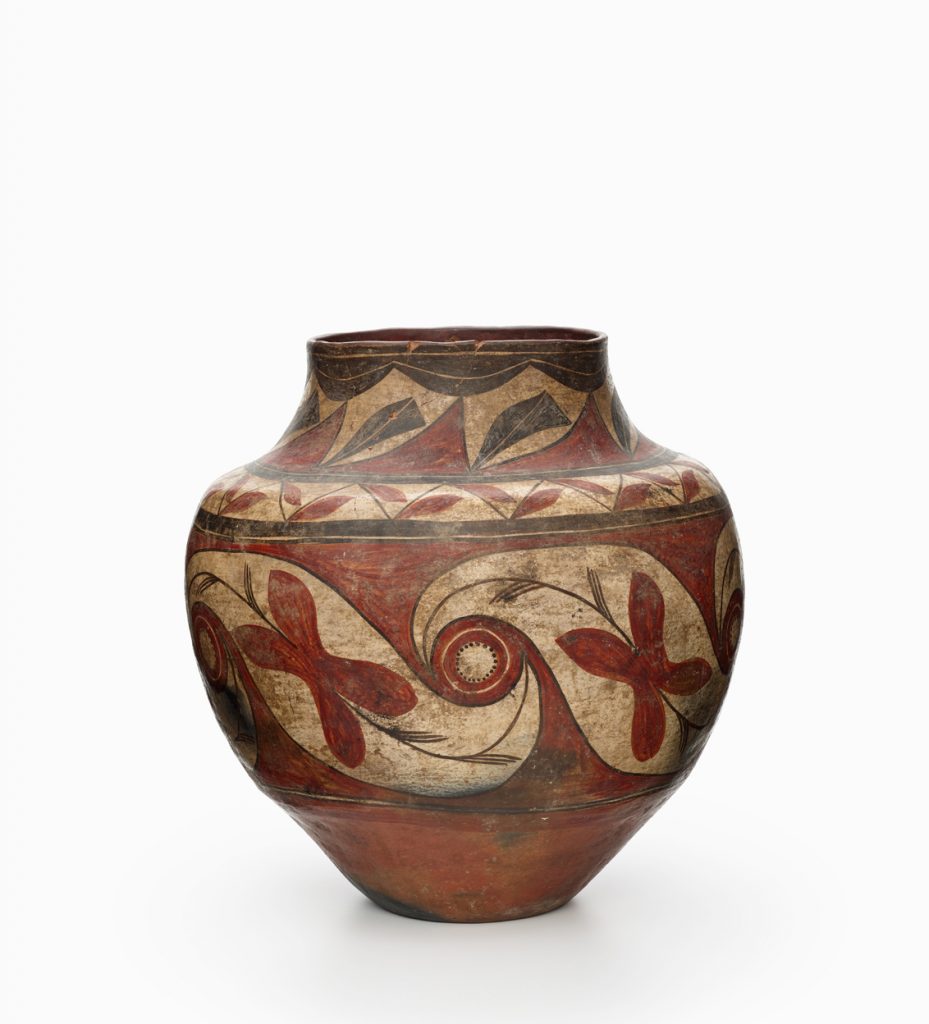

Samuel chose the following for the Grounded in Clay exhibit:

Web of Life

Despite what we have been led to believe, we humans are no more important for, nor less crucial to, the balance of the ecosystems in which we live than are our nonhuman relatives. This belief that we are separate from “nature” has put us and all other forms of life in a precarious position. In this colonized way of thinking, we act selfishly. Convenience outweighs responsibility. This Zia pot represents the alternative: thinking and living with intentions of balance. Encapsulated within it is the web of life, a web in which Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples play key roles.

I have chosen the path of learning and teaching the Tewa language, and, as I have traveled it, I have come to various conclusions as to what the point of it is. Leaps and bounds beyond the saving of a unique form of communication, it is worldview; it is ways of doing, thinking and believing, and, ultimately, survival. Speaking Tewa is an accomplishment and should be celebrated, but without an alignment of one’s actions with the values from which the language emerged, Tewa remains only words, exotic to outsiders. I am very much in the midst of navigating and understanding this alignment.

The context in which this pot was created was undoubtedly steeped in the traditions and Keres language of Zia Pueblo. And while we may never know exactly what the creator of it had in mind when they chose these designs and patterns, I do not think an understanding of their intentions is as important as the current viewer’s interpretation of what the pot has to share. For myself, I cannot help but see the web of life—those now unnoticed or seldom recognized connections and forms of interdependence between all living things. The potter worked with hand- harvested clay and various natural pigments to give birth to their pot, their child. They chose to show representations of what I see as pollination—wind and insects. The potter, wind, and insects engage in processes of creation, interdependent beyond what we might notice on the surface.

Western science is catching on; it tells us biodiversity is linked to linguistic diversity. But what are we doing to recognize and encourage this link? We must support, prioritize, and partake in Indigenous language revitalization efforts. Our Indigenous languages are land-based, so they can be found only where we are. They too convey the web of life and provide an entrance point to it, away from the colonized mind. But language revitalization is not a static endeavor. Either progress is being made, or the fight is being lost.

Fortunately, our languages push those who take on the challenge of carrying them on to go beyond the words and to reflect on their identities as a whole. What makes us community members? What are our intentions? Just as learning to make pottery can be frustrating and arduous, so too can the process of acquiring an oral-based language. But we are not alone. We have speakers and other knowledge-holders who want to share, just as this pot shares. They want to see us succeed, and so we must step up.